Phedre

In twelve words: Phedre wants her stepson, who wants his father’s enemy. Then everyone dies.

Let’s smoke cigarettes and talk about Racine, agency, and fate. Let’s. Say yes.

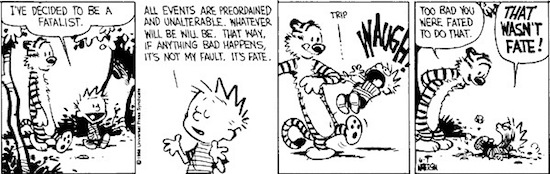

Que sera, sera. While science contests the feasibility of free will more vehemently (do you read these things?), it seems that the Enlightenment ideal of unconstrained individual thought is troubled by the public’s favoring more archaic models of consciousness. Ancient Indian philosophers insisted on an unavoidable karma, early Hebrews discussed “God’s will,” and the ancient Greeks deliberated upon moira. That’s fate, gentlemen.

So, let’s talk about Racine’s tragedy Phedre as a dark meditation upon the possibility of choice in the midst of fatalistic forces roaming far beyond the scope of individual control or even awareness. Fun!

The play, written and produced in 1677, sort of plagiarizes the tragedy of Euripides. Theseus, king of Athens, husband to the doomed Phedre and father to the unlucky Hippolytus, is away from his city. And good for him, because back home, there’s, like, drama drama drama.

While anxiously awaiting news of her husband, Phedre explains to her nurse, Oenone, why she’s been so mopey and whiny lately. Turns out she’s in love! Years ago, when she arrived at the court of Theseus a young, beautiful bride, she happened to turn around… and there he was.

Who was he? Well, here’s where it gets good. It was Hippolytus, her husband’s son. She fell in love with her stepson! Weird. Hippolytus, meanwhile, has problems of his own. He has an enormous crush on Aricia, the only survivor of a royal house which once warred against his father. He’s pretty upset about it because having romantic feelings for people who tried to kill your family is totally inappropriate.

Phedre and Hippolytus are both frightened that their respective emotions will make Theseus really, really mad. Because, you know, obviously. When the mistaken news of Theseus’ death unsettles the kingdom, Oenone urges Phedre to reveal her feelings to her stepson. After all, you aren’t related, and with Theseus gone, who knows what can happen? Go for it, girl. YOLO. Stupidly, Phedre tells Hippolytus the truth: “Your dad’s dead, so let’s get married.” Predictably, Hippolytus declines: “Um, no, let’s not.”

Soon after, Theseus arrives. He’s not dead after all! Great! It’s great, right? Wrong. Realizing that her husband is likely to find out about her incestuous betrayal, Phedre contemplates suicide. Oenone, who adores her mistress and is willing to sacrifice anyone to avert her punishment, suggests that Phedre accuse Hippolytus of attempting to rape her. Delirious with panic and becoming more and more incoherent, Phedre decides that this is a good idea. (Note: accusing people who have not assaulted you of assaulting you is never, ever, ever a good idea. Because of karma and stuff).

When Theseus confronts his son, Hippolytus is all, “Why would I want to sleep with that old hag? I’m in love with Aricia. You know, your nemesis, the one who tried to kill you.”

Then Phedre begins to feel bad for being such a jerk to Hippolytus. She decides to tell her husband that they should just, like, get past the whole rape thing and be friends. Before she has the chance, Theseus tells her, “Hey, Hippolytus in love with Aricia. You know, my nemesis, the one who tried to kill me.”

Blind with jealousy, Phedre decides against absolving the innocent Hippolytus. He’s in love with someone else? He can go straight to hell.

So Theseus banishes his son from the kingdom, and soon after, Hippolytus is killed by a sea monster. Seriously.

Phedre, in mounting panic, accuses Oenone of manipulation and disloyalty because the sea monster incident is totally her fault. Oenone thinks, gosh, I’m horrible. So she drowns herself. Then Phedre appears before Theseus to defend his son’s innocence and repent of her illicit passion. Sooo sorry, things just go a little out of control, you know how it is. Then she drinks poison and dies. That’s all.

The ways human beings use stories to structure experience and create meaning is the focus of narrative criticism, whose practitioners seek to understand how the deployment of symbols in narratives reveals or conceals aspects of the world. Utilizing the method of narrative criticism, let’s talk about how narrative can convey tension between agency and fate. Phedre’s setting and characters reveal how Racine succeeds in achieving this objective.

Setting

While the physical features of the play’s setting are negligible, the kingdom of Athens as situated within the overall sociohistorical context of ancient Greece is of supreme significance. Particularly since almost the entirety of the plot is borrowed from Euripides,

Phedre features the motifs and commitments of ancient Greek tragedy. Racine’s Phedre is set within the confines of a superstitious, paganist, fatalistic culture.

From Hercules, who murdered his own children at the will of ruthless Hera, to Oedipus, who was destined to kill his father and seduce his mother, the notion that fate determines human behavior is a guiding principle of ancient Greek thought. Phedre and Hippolytus, ensnared within such a culture, cannot help but reflect its beliefs and values, particularly in their relations to ancient Greek deities. The events which befall Racine’s heroes can only occur in a context wherein gods capriciously and even arbitrarily toy with human lives. Phedre consistenly summons the gods to witness her suffering at their hands.

Addressing her grandfather Helios at the opening of the play, she cries, “Noble and blazing Author of a race/ Of sad, unhappy mortals!” (Phedre 1.3). Soon after, she wonders: “Where, where have I let stray/ My longings and my self-control? Oenone!/ The Gods deprive me of the use of it” (Phedre 1.3). Prior to explaining her forbidden love for Hippolytus to her nurse, Phedre laments: “Your fatal hatred Venus! Oh, your wrath! … Since Venus wills it so, I perish now” (Phedre 1.3).

Similarly, when Hippolytus admits himself in love with Aricia, he asks, “Am I, in turn, to find myself enslaved?/ Can the Gods wish to humble me so far?” (Phedre 1.1). When grieving the death of his father, Hippolytus says, “The Gods at last have doomed him, even him/ Alcides’ friend, companion, and successor,/ To the homicidal shears of Fate” (Phedre 2.2).

Hippolytus and his father, the great Theseus, are both admitted to be the pawns of overwhelming forces. It is important to note that Theseus is a hero who is famed for slaying the Minotaur. He is not a cowering and frightened creature, imploring the decisions of the gods. He acts within the world with considerable freedom and power. Nevertheless, the gods can overpower “even him.” The “homicidal shears of Fate” do not distinguish between coward and hero. Theseus and Hippolytus are indeed strong decision makers, but only inasmuch as they are divinely ordained to be so. Such heroic greatness pursued within, rather than beyond, divinity’s constraints, is possible only to a citizen of an early civilization. The historical setting of Phedre, which juxtaposes individual will with fatalistic power, is chronologically ancient and hierarchically supernatural. The characters literally walk within a world of gods, demigods, and monsters. The active presence of gods which can condemn a Phedre and monsters which can murder a Hippolytus is a vivid demonstration of human choices conflicting with external forces.

Phedre is also ideologically situated within a seventeenth century, religious, Western culture. Much has been made of the Jansenism of Racine. Educated in the Jansenist community of Port-Royal, Racine was invariably exposed to Jansenist thought, which insisted upon humanity’s depraved nature caused by original sin. This inescapably fallen state reappears in Phedre’s dramatic inability to overcome the perversity of her own desires. Much like the Jansenist followers who could not overcome the stain of original sin and would be redeemed only by communion with God, Phedre seeks the resolution of her suffering beyond the horizons of ordinary possibility.

For the Jansenists, salvation was achieved through God’s grace. For the pagan Greeks, human transcendence led to death. In either case, Phedre reminds us that redemption cannot be found within the everyday round of human life. Furthermore, the setting involves a moralistic stance ushered in by the play’s reliance upon the incest taboo. Such love is presented as so monstrous that Phedre must die rather than endure it, and when the innocent Hippolytus stands accused of it, his horrified father banishes him from the kingdom.

The incest taboo emerges from the guarded parameters of sexual activity within society, undertaken as protection of familial and social organization. Sociologist Talcott Parsons writes: “It is essential to the family that more than in any other grouping in societies, overt erotic attraction and gratification should be given an institutionalized place in its structure … eroticism is not only permitted but carefully regulated; and the incest taboo is merely a very prominent negative aspect of this more general regulation.” The defining feature of the incest taboo is that it’s a prohibition. Its prohibitive nature means that incestuous behavior is always necessarily a violation of societal values and trust. Thus, what Phedre feels and what Hippolytus is accused of feeling are tantamount to rebellion, lawlessness, and destruction of the sociocultural fabric.

It is significant that Racine does not explain any of this. Phedre does not elucidate to the audience exactly why her passion for Hippolytus is an ethical failure, and Theseus does not elaborate upon why he is justified in banishing his son from Athens. For Racine, such values are implicit within the work and automatically assumed. Racine does not tell us how to judge his characters, and he expected his audience to arrive at the theater with a tacit moral understanding which they then applied to the events they witnessed. The modern reader still approaches the play with the unspoken awareness that a woman’s desiring her stepson is perverse, immoral, and unjustifiable. Thus, the play relies upon a wider sociohistorical context in order to communicate its message. Without this implicit moral awareness, the events of the play would be incomprehensible.

In a profound sense, then, the reader participates in structuring the setting of the play. Phedre’s setting is not simply prepared by Racine for the reader to step into – the reader also brings a set of ideological commitments which enable the play to function as a tragedy. It is precisely because of this ideological setting, which is simultaneously presumed by the audience and represented by Racine, that the characters and interactions become substantial and meaningful as manifestations of the struggle between human agency and inhuman forces. Phedre’s setting does not merely structure the play for the reader, but also delimits the possibilities for its characters in a way that illuminates the struggle for individual freedom.

The fatalism of Greek myth, the irredeemable human nature of Jansenism, and the ideology of the incest taboo, all implicitly conspire to make explicit an unassailable wall of abstract obstacles against which Phedre’s characters find themselves crashing.

Characters

The personalities and interactions of Phedre’s characters help facilitate Racine’s objective of presenting agency conflicting with fate. Phedre, Hippolytus, and Oenone are the principal actors whose critical choices determine and delimit events.

Phedre is remarkably single-minded and uncompromising. Her illicit love has consumed her utterly. As a consequence of her alleged impurity, she seeks death. Not, however, as a desired end, but as the unavoidable outcome of her true desire’s incompatibility with what is possible. Vera Orgel writes about Racine’s tragedy: “The greatest catastrophe is not the failure but the breaking of the mainspring of life, renunciation of the unattainable goal and the end of endeavor.” For Phedre, fulfillment is impossible: the very nature of her passion forbids its realization.  Phedre’s very being is at odds with life, and her tragedy is that she cannot change. She cannot simply “get over” her feelings, despite her recognition that they are a “crime,” a “malady,” and her “love is horrible,” and she would rather die than confess to “a love so black” (Phedre 1. 3).

Phedre’s very being is at odds with life, and her tragedy is that she cannot change. She cannot simply “get over” her feelings, despite her recognition that they are a “crime,” a “malady,” and her “love is horrible,” and she would rather die than confess to “a love so black” (Phedre 1. 3).

Her reason is intact, but her will is disobedient. What binds her so hopelessly, she is convinced, is the tyranny of a petulant Venus. Of course, whether there is actually a scheming Venus or not is beside the point. Venus or no Venus, the cruel conflict is clear: something beyond the limits of human possibility urges Phedre to seek that which is beyond the limits of feasibility. In this struggle, Racine casts the opposition of human agency and fate. What Phedre longs for is forbidden, and rather than overcome her weakness, she dies. To challenge the edicts of fate, Racine tells us, is suicidal. The Racinian hero is tragic inasmuch as his life remains eternally uncompleted.

When, deceived by the supposed death of Theseus, Oenone persuades Phedre to hope to marry Hippolytus, a veritable social disintegration threatens. For Phedre to achieve what she longs for, not only in the sense of possessing Hippolytus but in the wider sense of living publicly as his wife in a world wherein her violation of the incest taboo is acceptable, her entire social order must be undermined. After all, the incest taboo is the foundational law of the original social unit – the family – from which the wider sociocultural context emerges: the prohibition of incest is the original law which begets all other rules of civilization. Phedre’s nature, quite literally, exists against the world.

To dispel any possibility of self-realization even further, Racine reminds us that Phedre is the daughter of Pasiphae, who was cursed to procreate with a bull in the madness of her inhuman ardor. Even this horror, however, is presented as ordained by the gods. Phedre cries, “Venus! …/ Into what aberrations did love cast my mother!” (Phedre 1.3). Phedre’s monstrous fall is determined not only by the gods and the social edicts governing proper sexuality, but also by her parentage. Her mother’s “aberrations,” it seems, predict and perhaps even prefigure her own. In these myriad ways, then, Phedre is bound. She seems hopelessly doomed, which is precisely what Racine wants his audience to recognize.

Such fatalism, however, is not Racine’s only objective. He also wants to present the defiant blazing of human will in spite of fate’s closed doors. Irrational, hopeless, and pathetic as it may be, the tension between pre-determination and will emerges most poignantly in the very fact that Phedre dares to love Hippolytus in spite of every possible reason why she should not. In the simplest terms, she loves him “anyway.” After all, if human beings were mindless automatons able only to parrot their own boundaries, Phedre wouldn’t be capable of even conceiving of such a love. Her passion is proof of her freedom, however limited it may be.

Hippolytus, too, is fated to desire what is forbidden. In loving Aricia, he finds himself loving that which represents the violent destruction of his family: “That young sole survivor of a tribe/ Which fatally has long conspired against/ My family: Aricia” (Phedre 1.1). Furthermore, he knows his father will resent the match: “Did I forget/ The eternal barriers between us two?/ … Against the wrath/ Of an infuriated father, launch/ My youth upon a course of love so mad?” (Phedre 1.1).

Much like Phedre, however, Hippolytus protests that he is not to blame. Known as prideful and solitary, Hippolytus has scorned the snares of romance and women, preferring instead the less intimate arts of racing horses and hunting. However, something beyond his own reason beckons him to Aricia. He asks, “And even if my pride could ever melt/ Should I have been insane enough to choose/ Aricia for my conqueror?” (Phedre 1.1). The guilty love, Hippolytus explains, is not his choice. Now that he is captured, however, he regards Aricia as his “conqueror,” once more underscoring his helplessness in the romantic matter.

In great contrast to Phedre, however, Hippolytus is virtuous. The play’s characters know him for his chaste, monastic nature. He remains virginal and aloof, casting cool and superior glances at the warm entanglements of eroticism.  His tutor, Theramenes, describes Hippolytus thus: “So proud and wild,/ Making a chariot fly along the shore;/ Or, practiced in the art that Neptune taught,/ Taming unbroken horses to the rein” (Phedre 1.1). Hippolytus spends his days playing with horses and chariots — his interests, like those of a young boy, are childlike, innocent, and free from intrigue.

His tutor, Theramenes, describes Hippolytus thus: “So proud and wild,/ Making a chariot fly along the shore;/ Or, practiced in the art that Neptune taught,/ Taming unbroken horses to the rein” (Phedre 1.1). Hippolytus spends his days playing with horses and chariots — his interests, like those of a young boy, are childlike, innocent, and free from intrigue.

Furthermore, Hippolytus knows he is virtuous: “When I grew to riper years and knew myself,/ I praised, myself, the self I came to know” (Phedre 1.1). What is Hippolytus praising himself for? His “Amazonian pride,” (Phedre 1.1) which keeps him sexually pure.

When discoursing on the myriad accomplishments of Theseus, Hippolytus critiques his father’s wayward eroticism. He and Theramenes discuss how Theseus slew the Minotaur, displayed the strength of Hercules, and punished pirates. However, Theseus is not romantically consistent or honest, and Hippolytus laments his father’s “less glorious deeds/ His promise made and broken everywhere… Too credulous creatures by his love deceived… How happily I would have then wiped out/ The base half of so fine a history” (Phedre 1.1). His father’s past, Hippolytus complains, is “base.” He regards himself as enough removed from such impurity to be able to judge it accurately. Fifty years ago, Hippolytus may have been described as a prig. Precisely because of such self-conscious goodness, Hippolytus does not garner the audience’s compassion as the self-deprecating Phedre does. We admire his scruples, of course, but we can’t quite grasp why Phedre loves him. We certainly can’t.

Given Hippolytus’ aggressive goodness, it’s all the more remarkable that someone as rigid as he is could possibly fall into the snares of erotic love. Theremanes, guessing at his charge’s passion for Aricia, asks, “What heart has ever been too brave to be/ Vanquished by Venus?” (Phedre 1.1) and later cries, “What is your pretended pride of speech?/ Confess it, all has changed!” (Phedre 1.1). Hippolytus cannot maintain his own scornful nature, because the gods do not will it so. If it were up to him, he would continue to race and play along the shore, contemptuously frowning at the impious desires of others. Instead, “all has changed,” and he finds himself bound to love his enemy.

Just as with Phedre’s powerful emotion, the guilty love of Hippolytus for Aricia displays not only his helplessness, but also his paradoxical freedom. Love changes him. Only emotionally flexible beings are capable of change, of response to the bursting and raving of circumstance. He does not remain static and stubborn, like a fixed sculpture or a puppet, but exists in subjective relation to other subjects. Even he, the audience is led to think, the proud and solitary monk, can suddenly begin to burn with a very human feeling. Significantly, his humbling transformation softens him in the audience’s eyes, as well. Suddenly, Hippolytus ceases to be a self-aggrandizing demigod who pushes us away with his self-righteous bragging, and becomes a sympathetic character, whose dreams we support. From one perspective, the alteration Hippolytus undergoes is proof of how buffeted and controlled by fate he must be. However, it is also evidence of his great capacity for daring, for defying, for transgressing authority’s boundaries and his own stubborn nature. After all, he didn’t simply fall in love with a nice, acceptable girl his father might have liked. He fell in love with his family’s nemesis, a love he must denounce and yet cannot. In these paradoxical, seemingly contradictory ways, Hippolytus, too, is a study in the tense hues of agency’s struggle against fate.

Perhaps the freest character in the tragedy is Phedre’s nurse, Oenone. It’s important to mention Racine’s own preface to the 1677 publication of Phedre. He explains that although the original Euripides play featured Phedre coming to the decision to accuse Hippolytus of rape on her own, he decided against casting his heroine in such a merciless light. Racine explains his decision: “I have taken the trouble to make her a little less hateful than she is in the ancient versions of this tragedy, in which she herself resolves to accuse Hippolytus. I judged that calumny had about it something too base and too black to be put into the mouth of a Princess who for most of the time is only noble and virtuous.” But is this convincing?

Also, whereas the Euripidean Theseus learns of his son’s innocence after conversing with a goddess long after Phedre’s suicide, Racine generously insists that his noble heroine herself inform her husband of the truth. If Phedre is absolved of too much cruelty, then who will be to blame? Well, Racine clarifies, “This depravity seemed to me more appropriate to the character of a nurse, whose inclinations might be supposed to be more servile.”

Thus, the ultimate dichotomy between Phedre and Oenone is established, as between master and servant, elite and common, noble and depraved. In some sense, Oenone is trapped by her lowly circumstance. She is destined to remain socially inferior by virtue of her rank and occupation. In a different sense, however, Oenone’s lack of courtliness prefigures her greater freedom. While Phedre accepts insurmountable obstacles, bemoaning the wickedness and unfairness of divine inevitability, Oenone fights against the tide of circumstance. Less bound to royal duty, Oenone’s life instincts can burn more surely. Contrasting the two characters, Thomas Braga writes: “Oenone’s ‘oeil vivant,’ basically pagan, existential, energetic, pragmatic, a life-oriented point of view, contrasts vividly with Phedre’s ‘oeil mourant,’ essentially Jansenist, pessimistic, guilt-ridden, lethargic, and moribund.” There is dignity in suffering, Racine seems to tell us, and even more dignity in accepting it. Oenone’s alleged servility is correlated directly with her unwillingness to suffer. Or, to put it more boldly, it is correlated directly with her unwillingness to submit to fate.

Despite Phedre’s adulterous and incestuous desires, it is Oenone who is accused of ushering in the kingdom’s doom, which kills Phedre, Hippolytus, and Oenone herself. Why? Precisely because Oenone is the prime mover of the action – indeed, she is the one who chooses, and urges Phedre, to act. After hearing of Theseus’ rumored death, Oenone argues, “By Theseus’ death all knots have been untied/ Which made your love a horror and a crime./ You need no longer fear Hippolytus” (Phedre 1.5). From whence comes this radical meddling? Is it truly from Oenone’s “servile” rank?

The play’s events belie Racine’s own judgment in his preface.

At the opening of the play, Phedre is overcome with grief and guilt, longing only for death. Oenone will not hear of it: “Although only a feeble ray of life/ Remains with you, yet sure I will forestall/ Your voyage to the dead, and get there first” (Phedre 1.3). After the failure of her various attempts to boost Phedre’s spirits and alter her decision to die, the desperate nurse scrambles to think of some other plan to keep the queen alive. Seizing upon the news of the king’s death, Oenone explains: “Madame, I ceased to urge that you should live;/ I thought to follow you into the grave/ From which I had no more the heart to turn you;/ But this new blow prescribes for you new laws” (Phedre 1.5). In begging her to approach Hippolytus and consider marrying him, Oenone is acting to prevent the death of Phedre. If marrying Hippolytus will make her queen content, Oenone will enthusiastically urge the possibility. When the kingdom learns that Theseus is alive and Phedre once more returns to her melancholy refrain of suicide, Oenone begs her to live for her son: “Think of a son whose only hope you are” (Phedre 2.5). When that calculation fails, Oenone grasps at what seems like an avenue to Phedre’s liberty: “Be bold, accuse him first!/ Charge him with the same crime of which today/ He can accuse you!” (Phedre 3.3). With this temptation, Oenone buries herself in dishonor and is rightly regarded as bringing about Phedre’s suicide and Hippolytus’ murder.

The question, nevertheless, remains: is Oenone’s motivation base and unworthy of a “noble Princess?” The activities of the nurse reveal that her motive is far from depraved and, in fact, functions at the highest level of compassion and loyalty. She cries, “Alas! Whether I be to blame or not/ For your misfortunes, what is there on earth/ Of which I am not capable to save you?” (Phedre 3.1). It is not from inferiority of rank that Oenone acts so magnanimously, but from her greater sense of agency. Despite the edicts of the gods which doomed Phedre, Oenone struggles to transcend them and bring about a state of satisfaction and happiness. Indeed, Oenone’s is the most active, striving, willing role in the play. Phedre only languishes and laments, while Oenone fights to grasp the reins of fate and alter its direction. Of course, the nature of Racinian drama must frustrate her work. The profound compassion motivating her struggle must become a tacit accomplice in a predetermined mercilessness. It is not Oenone’s inherent inability to be ethical, but rather the inhumane brutality of the gods, which is the source of Phedre’s downfall.

This is how Racine reminds us that human will counts for very little in the powerful surge of uncontrollable circumstance. Nevertheless, while Phedre and Hippolytus dare to live against fortune only in their inward, guilty, erotic worlds, Oenone defies laws and events in the sphere of the everyday. In seeking to marry Phedre and accuse Hippolytus, thereby privileging sensual happiness above social duty, Oenone subverts the incest taboo, the fatalistic Greek value system, and the guilty Jansenist conscience. She contests the rules of what is acceptable, good, and just. Oenone is the only character who truly acts and whose decisions provide most of the impetus for the play’s events.

Phedre’s ancient, pagan, ideologically rife setting, influenced as it is by Racine’s strict Jansenism, becomes a powerful symbol for the intractable trappings of fate. The three most significant characters – Phedre, Hippolytus, and Oenone – are enmeshed in a world largely not of their choosing. With their futile struggles and profound melancholy, Racine paints a world wherein human will has little influence. Oenone, the most daring and free character in the play, may be justly regarded as subverting this bleak picture. Of course, in a more profound sense, it is Oenone’s seeming agency that brings about Phedre’s death, thus linking her into a fateful chain which she cannot tear asunder, either. Even the character with the greatest freedom can only contribute to a fated end. Nevertheless, the struggle for love and happiness, simultaneously foolish and great, permeates Phedre’s theater. Even as the wills of the characters are frustrated again and again, a perhaps irrational defiance underwrites their tragedies. Human freedom, it seems, is sometimes simply a matter of stubborn faith. By aesthetically intermingling the play’s setting and characters, Racine’s narrative is able to convey the fragility of freedom.