Thomas Mann

Death in Venice

Thomas Mann

In twelve words:

It is not possible to summarize this book in twelve words. Sorry.

I think:

Whenever someone asks, “What’s this book about?” they expect an answer like “Character X does Y and then Z happens.” Like, Voldemort killed Harry’s parents, but then Harry’s disarming curse killed Voldemort and all was well.

In other words, they want the plot.

When it comes to good literature (and no, that doesn’t include Stephen King or Harry Potter or even Twilight — hate me, I’m snobby), the plot is never what the novel is “about.” Death in Venice is really, really, really not about the plot.

Though short, it’s an extremely complicated, lyrical, philosophical exploration of the nature of art,  beauty, passion, and the role of the artist in society, and it’s brimming with intertextuality. <—this is a fancy term for “references to other literary works” and although it makes you sound really smart, don’t use it often because it only impresses literature grad students, and who wants to impress them?

beauty, passion, and the role of the artist in society, and it’s brimming with intertextuality. <—this is a fancy term for “references to other literary works” and although it makes you sound really smart, don’t use it often because it only impresses literature grad students, and who wants to impress them?

So, once upon a time (what time? I don’t know. Early 1900s), there lived a writer named Gustav von Aschenbach. He’s proper and virtuous and solitary and dignified and has an excellent work ethic and is, in other words, unforgivably dull. He’s also extremely successful – his books sell, he’s respected, he’s well known, he’s a big deal. He writes about characters who are as moral and uptight as he is. You know, virgins, saints, Superman. Anyway, on a sudden, mad whim (and it isn’t like Gustav to have any kind of whim, ever), he travels to Venice, Italy where he encounters Tadzio, a beautiful young boy. At first, he is enamored with Tadzio’s beauty since it inspires his writing.  But theeen, our Gustav becomes obsessed rather than just inspired, and begins stalking Tadzio and fantasizing about his boyish sexiness in all sorts of inappropriate ways.

But theeen, our Gustav becomes obsessed rather than just inspired, and begins stalking Tadzio and fantasizing about his boyish sexiness in all sorts of inappropriate ways.

Creepy? Disturbing? Disgusting? Of course. That’s the point. In the meantime, a cholera epidemic breaks out in Venice, but the Italian government officials and business owners conceal the danger from tourists because, you know, they’re ruthless capitalists and it’s all about the money, honey.

Ashenbach finds out about the cholera, and briefly considers warning Tadzio’s family. In a burst of dishonorable cruelty, he decides against it: if Tadzio’s guardians find out about the epidemic, they’ll take him away from Venice and then he’ll have no one to stalk. Unthinkable. Aschenbach understands that Tadzio might die, but at this point, he’s so obsessed and twisted and perverted, he doesn’t even care. He just runs around the diseased city, daydreaming about Plato, getting his hair curled, and eating strawberries.

He also has inappropriate dreams: one night, he dreams of a chaotic orgy, with hordes of screaming, nude women and swarms of men beating drums.

This is not your typical Playboy pool party. This is perverted and disturbing and violent and dark.

This is not your typical Playboy pool party. This is perverted and disturbing and violent and dark.

Finally, one morning, while staring at Tadzio and pretending they have some sort of romantic thing going on, good old Gustav dies. That’s how it ends. He indulges in one last, dirty fantasy for the road, and then kicks the bucket. Just like that. So, that’s the plot.

However, next time you’re at a cocktail party and the guests are being sophisticated and pedantic and brilliant and someone asks, “What’s Death in Venice about?” thou shalt not say “A disgusting old dude who wants to screw a young kid.” That will not impress anyone who isn’t stupid because that is not what the book is about.

So what is it about? Well, in figuring that out, the first question one might ask is, why a young boy? Why couldn’t Aschenbach fall in love with a nice lady his own age and have a healthy relationship with a consenting adult?

Significantly, Mann said: “In Death in Venice I wanted to present a man who at the summit of success, fame, and fortune finds no refuge in art but instead runs around, physically and psychologically, on an insurmountable passion… Only to make the plunge from the summit into the depths appear as fateful as possible did I choose for my hero homosexual love.”

So, the creepiness and inappropriateness and pervertedness of Aschenbach’s obsession is exactly what we’re supposed to be noticing. Wow, Mann wants you to say, this guy is really, truly, super-duper nutty. He was all monkish and boring and then, wham, bam, thank you ma’am (who doesn’t love a Bowie reference?), he’s a pedophile! But why did Mann want that to happen? Well, hold your horses, I’ll get to that. Let’s explore some of the general ideas, themes, and allusions in the book.

- Dionysian and Apollonian Opposition.

So, a fabulous thinker named Nietzsche (the indisputable rock star of philosophy who cannot be categorized) described the world and the fundamental nature of the human condition as consisting of two opposing elements: the Dionysian and the Apollonian.

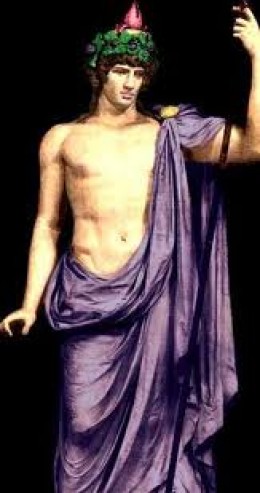

Dionysus is the Greek god of wine, intoxication, and ecstasy –he’s associated with music.

Apollo is the god of the sun, dreams, and reason (think of light and order) – he’s associated with sculpture.

More importantly, the Dionysian is reflective of the amoral, eternal, chaot ic, dark heart of nature itself. Life, Nietzsche thinks, is a primordial, willful striving, but it doesn’t strive for anything. It’s aimless. It just strives. Keep in mind that “life” here needn’t be carbon based. Nietzsche means anything that exists. Rocks, meteors, hydrogen molecules… just the stuff of the world.

ic, dark heart of nature itself. Life, Nietzsche thinks, is a primordial, willful striving, but it doesn’t strive for anything. It’s aimless. It just strives. Keep in mind that “life” here needn’t be carbon based. Nietzsche means anything that exists. Rocks, meteors, hydrogen molecules… just the stuff of the world.

In this forceful aimlessness, all distinctions and particulars are swept into the eternal movement of life itself. It’s not confusing, I promise.

Think of it this way: you’re born, you go to school, you stress over which career to choose, decide you want to be a doctor or a criminal or a priest. Then you’ll have three children or a BMW M3 (these are mutually exclusive categories), and your colleagues will think you’re swell and you’ll think you’re amazing! And you are amazing! You received the Nobel Prize for inventing the CCD image sensor!

And then… you’ll die. And it won’t matter. Sure, some people will remember you, and some will even cry. But then, they’ll die, too.

Forget the Nobel Prize. Let’s say you’re Augustus himself and you stand at the founding of the Roman Empire. Guess what?

Augustus is dead.

The Roman Empire is gone.

The continuous force of life has swept one of the greatest civilizations into oblivion and, eventually, all civilizations will fade away and humanity itself will disappear and life will go on blindly striving, pushing, pulsing, aimlessly, eternally.

Think of Shelley’s Ozymandias.

It’s a sobering thought.

Fundamentally, there’s only a blind totality and it’s an undifferentiated totality, where no individual entity or person or flower actually exists. At bottom, it’s all the same stuff, it’s all life just moving and moving and moving. Sound depressing? It is. It’s supposed to be.

BUT here’s the good news: we have the Apollonian! The Apollonian can be thought of as humanity’s response to the aimless indifference of nature. In spite of it all, humans can create distinctions between things, like good or bad, and they act as if individuated entities exist. We build monuments and shrines for Augustus and Homer and insist that heroism and achievement is important, that it’s a big deal that you became a doctor and that your daughter took her first step and that your wife left you last Saturday. We know we’ll die, we know it’ll all come to an end, but we go on and plant roses and study medicine anyway. Why? Because of the Apollonian force. The Apollonian is an illusion, but a beautiful, noble, necessary illusion.

If it weren’t for the Apollonian, we’d be nauseated at the thought of striving for anything in the face of the blind indifference of life. We’d be paralyzed and deny our will and do nothing, ever. Nietzsche thinks that’s very bad. It’s why Camus and Sartre smoked so much.

We have Apollonian illusions to counter the terrible Dionysian truth that nothing we do actually matters.

Now, for Nietzsche, the best art requires the precari ous balance of both forces. Too much of Apollo, and your work and your experience become stilted and formulaic and regimented and too serious – lacking life force. Too much Dionysius, and your work risks becoming incomprehensible, chaotic, meaningless. Both are necessary. Both are wisdom.

ous balance of both forces. Too much of Apollo, and your work and your experience become stilted and formulaic and regimented and too serious – lacking life force. Too much Dionysius, and your work risks becoming incomprehensible, chaotic, meaningless. Both are necessary. Both are wisdom.

So. Back to Ashenbach. He’s organized, moral, hardworking, solitary, over-achieving… he’s boring! He’s waaaay too Apollonian! He needs to lighten up, man. So what happens? He gets the sudden, random urge to travel. Suddenness, spontaneity, irrational whims? Dionysius was here. Then, Aschenbach falls for a child. Inappropriate and overwhelming sexual forces? Dionysius was here. In other words, Dionysius has come to reclaim the unbalanced Aschenbach from his entirely Apollonian existence.

Balance must prevail. Aschenbach – and indeed any human – cannot get away with masking from himself the true nature of reality for too long. The art Aschenbach creates must reflect the Dionysian force.

Remember Aschenbach’s dirty dream, with the mass orgy? It symbolizes the Dionysian Mystery cults of ancient Greece, where participants used intoxicants and music to deliberately induce trances and overcome societal limitations.

It’s kind of like a rave, but more philosophical. The point was to effect a dissolution of the self, to commune with the god. However, Nietzsche explains, the Greeks had such festivals precisely because they were carefully regulating the Apollonian-Dionysian balance. They didn’t want to be overly Apollonian. They understood the danger of becoming too reasonable and sterile. So, they indulged Dionysian urges, but they did so wisely and thoughtfully. Had they completely submitted to Dionysius, their culture would crumble beneath the chaotic violence of an existence without organization or obligations.

Imagine what would happen if you didn’t have concepts such as “good” or “evil”, if there was nothing that you felt was unacceptable, if you recognized no distinctions or individuals or limitations. What would you do? Well, like Oedipus, you might sleep with your mother and murder your father. Quit your job? Sure. Crash your car? Why not? Rob a bank, set fire to your house, throw yourself from the roof a skyscraper. Whatever.

You see, recognizing that you can’t fly, or that killing is wrong, or that sleeping with your family is gross, is always a recognition of a limitation, or an ethical norm, or rules like cause and effect.

For Dionysius, there are no such distinctions or limitations or norms. Everything is permitted. Consequently, everything is destroyed.

But, remember, that’s not a problem for the god! The pulsing force of life will go on. Whether you are dead or alive, it’s no concern of the sublimely indifferent Dionysius.

So, essentially, that’s what’s happening to Aschenbach. His culture – his stature as a successful writer, as an ethical and regimented human being – is unraveling. And the god does not care.

- Greek Idealization of Male-Male love.

It’s not what you think.

Let’s return to the Greeks. Once upon a time, it was completely normal, particularly for purposes of education, for young teenage boys to engage in erotic relationships with much older men (thus demonstrating the social constructedness of sexual desire, but that’ll be a different post).

Aschenbach’s feelings for Tadzio reflect this tendency. Tadzio plays the role of the young, objectified erômenos. He is not a human being. He is a beautiful object, existing not for his own sake, but for the use and pleasure of others.

Initially, Tadzio serves the purposes of inspiring Aschenbach’s writing – he’s an aesthetic object. Then, Tadzio becomes the source of Aschenbach’s fantasies – he’s a sexual object. But as far as Tadzio’s basic humanity is concerned, Aschenbach absolutely doesn’t care. The boy might die from cholera. Hey, man, whatever.

- Platonic Theories of Beauty.

Sorry, more Greek stuff.

Plato, to whom all of Western philosophy is but a footnote, has a crazy and beautiful conception of truth. For Plato, true knowledge is gained by progressing from shadows and copies of things to the original things themselves, which are essences.

So, for example, you see a basketball, an orange, and a clock.

What do they have in common? Well, obviously they’re all round. To sound a bit more academic, they all possess the property of roundness. Plato would say that roundness itself is an actual thing which exists in a separate realm. This applies to all properties of things. So, tableness and squareness and deliciousness and catness all exist in that separate dimension, and it is by virtue of this dimension that we find objects with table-like properties (tables) and objects with square-like properties (boxes, let’s say) and objects with properties of deliciousness (sushi) and objects with properties of catness (cats, usually).

Does this sound strange? If it does, it’s okay. It means you’re getting it. Plato is supposed to seem strange. It’s part of his charm.

Anyway, if you seek knowledge, Plato tells you, begin with contemplating an orange. Then compare the orange to the clock, then to the basketball. Recognize that they all share in the concept of roundness. Recognize that oranges and basketballs are imperfect manifestations of the essence of roundness. Now, abstract from the separate objects and think about roundness itself. In other words, intellectually ascend to the separate dimension and hang out there for a bit, among the essences and properties. Check out tableness and catness. Dwell on their abstractness, their completeness, their sublimity.

Can you do that? If so, congratulations! You’re a philosopher.

Can’t do it? Enroll in business school.

The same process of abstraction applies to beauty. Physical, sensual beauty is a manifestation of the eternal essence of beauty. Tadzio, then, is the imperfect copy of the essential form of beauty in itself.

In the super-cool dialogue Symposium (yes, I do think Plato is “super-cool” and yes, as a matter of fact, I do have friends), Plato describes the Ladder of Love, the ascent of which becomes increasingly more abstract. It begins with sensual love of a body and ends with beauty itself.

There’s the problem: Aschenbach begins AND ends with Tadzio’s body. In other words, instead of progressing from Tadzio’s particular beauty toward the essence of beauty (which is hanging out with the essence of roundness, remember), Aschenbach gets stuck in the physical plane. He doesn’t abstract from the roundness of the oranges and basketballs, like Plato advises. He just stays grounded, making orange juice and shooting hoops. Getting stuck among objects, rather than contemplating their eternal essences, is the opposite of knowledge.

And that’s what the novel is trying to tell us. Rather than being purified and ennobled by his love, Aschenbach is degraded and belittled by it. What should he have done? He should have applied Tadzio’s beauty to his art, moving from physical properties to aesthetic elements. For Plato, sensual love is a stepping stone on the way to something higher. But Aschenbach doesn’t get higher. That’s the point. He’s stuck.

- The Role of the Artist.

So, at the beginning of the novel, Aschenbach’s art behaves as the detached arbiter of morality. The heroes he creates are famous for their perseverance and self-command. However, as Aschenbach suffers the throes of erotic love and succumbs to Dionysian forces, his aesthetic views change from stoic reserve to passionate, chaotic freedom. He comes to realize that artists live in a world of the senses. The artist is a bohemian, an amoral libertine.

Think of a rock star. His tastes, his activities, his life. Does the rock star live in seclusion and peace, somewhere where the air is fresh and the water is chlorine-free? Does he wake up early and take a cold shower? Does he drink warm milk before bedtime and swallow two gummy vitamins with each regular, plant-based meal?

No!

The rock star is unshaved and unwashed, sleeping with everybody, taking drugs and risks and names, contemplating suicide, destroying guitars, refusing no poison, hating the world. All these behaviors are permitted to him because he is a rock star (oh, Kurt Cobain…). In fact, these experiences tend to emphasize the intensity and power of his music.

Aschenbach has been living in sterile and unnatural seclusion his entire, Apollonian life. But it’s time for him to throw on Converse and a ripped pair of jeans, seduce some groupies, climb in a spray-painted van, and hit the road. He must learn desire and joy and suffering.

Does this mean that Mann suggests that artists are necessarily passionate, immoral sinners? No. Remember, Mann punishes Aschenbach for his perversion.

Does this mean that Mann suggests that artists ought, instead, to be reserved and detached moralists? No.

Perhaps it means that art demands both detachment and passion, both intellect and profound communion with life, to flourish.

So, there you are. It’s a lot, I know. And it’s not easy, I know. But I’m suspicious of simplicity as a regulatory ideal in writing or thinking. I see no reason to put simplicity on a pedestal, and I distrust simplicity for simplicity’s sake, especially where the subject matter is complicated and subtle. A straightforward explanation would neglect an enormous remainder, even as the above summary does. So, in simple terms, what’s the point of the book? Aesthetic decline, I think. But what do I know?