How Ancient Greeks Remember: A Thoroughly Unresearched, Unprovable, Untenable Hypothesis

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” -Faulkner

Let’s pretend you misplace your car keys, your phone, your lip gloss. What do you do? Most likely, you pause and try to remember what you were doing, where you were, when you last used the missing object. You re-collect — collect again — relevant fragments of the past, bringing them into the present and thereby making the past present once more. Re-collect and re-create to re-live. This sort of remembering is an internal and solitary experience.

Now let’s say that you anticipate the possibility of forgetting something, so you make a note for yourself:

*pick up mangoes

*text Lina about project

*Zimri-Lim owes the city of Babylon seven hundred sheep

Such administrative reminders prevent the past from slipping away in the first place, keeping the relevant information in a perpetual limbo to be retrieved any time.

But the act of recollection is a historical phenomenon, which means that not everyone has always remembered the way that we remember. Premodern oral cultures, especially song cultures, recalled the past by means of metered verse. In Homer’s time, the song of the bard wasn’t simply entertainment or art, although it was certainly both of these things. Song was the means by which a community made the past present again. The singing bard invoked the Muses to guide him in recollecting the deeds of heroes, thereby reminding the community of who they were and are. It’s a public, shared, communal act wherein the song is more than the content of what has been recollected: the performed song is recollection itself.

So how did Homer’s songs recollect?

Let’s talk about memory, cultural identity, and heroes.

The Iliad makes the past present while simultaneously re-interpreting and re-imagining it, curating a historical vision which simultaneously conveys a sense of nostalgia for a lost social structure and subtly critiques the current one. It reaches beyond performance into the philosophy of history to facilitate collective remembering.

How?

First, let’s lay our scene.

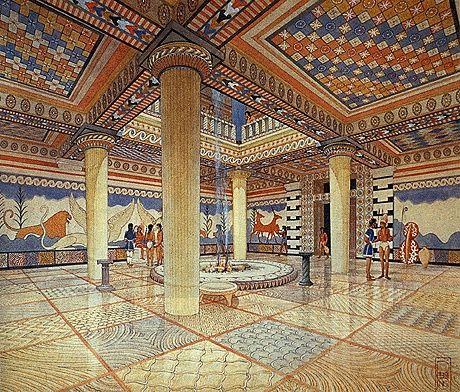

During the turbulent 12th century BC, the entire Aegean was deeply and brutally shaken by economic, political, and social crises which led to the collapse and disappearance of the gorgeous Mycenaean culture (my very very very favorite ancient civilization).

Hostile invaders from the north, environmental catastrophes, and a thousand causes scholars continue to debate saw site after site descend into charred ruin.

By 1000 BC, the stable, highly organized civilization of grand palatial complexes, warrior aristocracies, traditional wall-painting, ivory and gold-working, and sophisticated infrastructural projects had vanished.

This sudden, violent devastation ushered in centuries of depopulation, illiteracy, collapsed trade and administrative networks, and deep uncertainty. Imagine widespread draught, famine, and wars. Oh, things were grim.

This might be when the legendary and mysterious Sea People arrived, likely fleeing their own collapsing societies, invading and destroying struggling cities across the Mediterranean. The last communication from the doomed king of Ugarit, which made me cry the first time I read it, is a heartbreaking plea not for help but for acknowledgment of loss:

When your messenger arrived, the army was humiliated and the city was sacked. Our food in the threshing floors was burnt and the vineyards were also destroyed.

Our city is sacked.

May you know it! May you know it!

Even if the recipient of this message can do nothing, the king nevertheless demands for someone to know, to bear witness, to literally bear the unimaginable burden of such knowledge, so that the monumental destruction of his beloved city will not be forgotten.

Worst of all? Four hundred years of illiteracy followed the Bronze Age collapse. Messages from desperate kings were no longer sendable or readable.

Imagine living in 8th century BC Greece, a world of illiterate peasants and rough wooden houses, occasionally stumbling upon the ruins of majestic and monumental palaces.

What on earth are these incredible places and who were the giants who built them? What sort of superior beings lived in them? Where did they go? How were they destroyed? What the hell happened here?

What prevails is the trauma of not being able to remember. You cannot know what happened, you have no means to recollect it. Your past is simply missing. Four hundred years of silence. It’s disorienting, at best.

Because Iron Age communities could not re-collect the the Bronze Age by reading about it, they crafted a different way to remember.

In the 8th century BC, tombs filled with Bronze Age weapons and treasure were discovered, coinciding with Greeks’ growing awareness of themselves as both distant and different from those predecessors who had built the awesome fortifications of Tiryns and Mycenae. This newfound interest might be regarded as an embryonic historical consciousness, a self-awareness situating itself into a temporal context, relating and comparing itself to non-mythological ancestors which became the source of the rise of tomb and hero cults.

While the discovered warrior burial customs and Bronze Age iconography seemed to confirm the existence of “heroic” predecessors and the recovered precious objects circulated in the Aegean through trade and gift exchange, a search for evidence began in earnest.

Such deliberate pursuit was coupled with received oral memories of remarkable people who lived at the end of the Late Bronze Age and this construction of the heroic ideal was also either preceded by, followed, or was simply contemporaneous with, the creation of the Homeric epics. Whether the epics arose as a response to the hero cults or vice versa is not as important as their interrelationship at a time when Iron Age Greece became conscious of the enormous loss it had suffered with the destruction of Mycenaean civilization and began healing the trauma of this loss by the creation of a burgeoning, distinctive cultural identity which took its measure from an illustrious and spectacular heroic race.

Evoking and concretizing this identity, Homer’s narratives spread. By the 8th century, writing had been rediscovered, and Iron Age Greeks could finally set down the epics, or portions of them, thereby ensuring their distribution to an even greater audience.

Centuries later, the revival of national feeling was again inspired by the epics’ panhellenic nonpartisanism. Not only does the Iliad not privilege the Greeks at the expense of the Trojans, but it also presents a reverie of inclusiveness wherein the perpetually squabbling city-states are unified by a common purpose and harmonious in their common culture in a way they never were or could be.

For the fratricidal Greeks, this fantasy of unity has a particular poignancy, and with the suppression of the Persian threat, it becomes political dynamite.

Of course, it was that same Alexander who claimed descent from Achilles, performed sacrificial rituals among the ruins of Troy, and slept with the Iliad under his pillow in whom the Homeric spirit of shared values inspired the most successful attempt to create a Greek identity that transcended all ethnic and cultural boundaries.

To summarize, then, the development of Homeric epic, along with hero cults, accomplished three things:

- Simultaneously facilitated consciousness of a sense of loss and provided a means for overcoming this loss by remembering the past and recovering a distinctive identity;

2. Legitimized the old elite vanguard and the new polis structure;

3. Created a sense of socio-political unity.

The latter two can be approached as deliberate and essentially political, possible because of the former, which stems from the very nature of epic as a mode that creates the conditions for a shared past which can then be wielded as an instrument. Iron Age Greece was writing history by rewriting it, attempting to control collective memory by appropriating Homeric epic which itself was a recollection and reconstruction of inherited narratives, proceeding by intuiting, expanding upon, and crystallizing a sense of loss into a sense of nostalgia for a lost civilization.

This is possible because the Iliad is not exclusively an epic if we understand epic as what Paul Merchant described as “a chronicle, a ‘book of the tribe,’ a vital record of custom and tradition, and at the same time a story-book for general entertainment.” This common-sense definition is an amalgamation of the literary, the mythical, and the historical which gets established into culture as a constant reference point. Certainly the Iliad is all of these things, but it is something else besides.

In Book VI, Helen tells Hector that she pities the two of them “on whom Zeus set a vile destiny, so that hereafter we shall be made into things of song for the men of the future.”

The song she means is, of course, the Iliad itself. This self-reflexive remark momentarily estranges us from the narrative to remind us, just as it reminded its Iron Age audience, that the present story is not present at all and that the “men of the future” are us, now, in the moment of hearing or reading.

Later in the same book, Hector tells Andromache:

For I know this thing well in my heart, and my mind knows it:

there will come a day when sacred Ilion shall perish,

and Priam, and the people of Priam of the strong ash spear.

We read this from a vantage point of advanced knowledge, already knowing Troy’s fate. Homer’s audience, acquainted with Mycenaean palaces ruins, knew it, too. Hector’s prophecy has, for the audience, the quality of lament which arises from and is made possible by the self-consciousness of the text.

Perhaps most striking, however, is the passage in Book XII which describes the destruction of the Greek wall, emblematic of Greek strength, by referencing the future explicitly:

So long as Hektor was still alive, and Achilleus was angry,

so long as the citadel of lord Priam was a city untaken,

for this time the great wall of the Achaians stood firm. But afterwards

when all the bravest among the Trojans had died in the fighting,

and many of the Argives had been beaten down, and some left,

when in the tenth year the city of Priam had taken

and the Argives gone in their ships to the beloved land of their fathers,

then at last Poseidon and Apollo took counsel

to wreck the wall, letting loose the strength of rivers upon it…

where much ox-hide armour and helmets were tumbled

in the river mud, and many of the race of the half-god mortals.

The demise of the wall and the heroic race is described by once again removing us from the narrative. This collapses the aesthetic distance between ourselves and the present moment, replacing it with a historical distance between ourselves and the heroic race. We’re transported beyond the immediate, here-and-now immanence of the text’s temporal horizon and reverted to our own here-and-now, forced to reflect upon the narrative as narrative.

We are no longer spectating an imaginary story — we become aware of ourselves as the inheritors of historical ruin. This melancholy self-consciousness transcends epic’s status as “vital record of custom and tradition” and certainly that of “story-book for general entertainment.”

Everybody, this isn’t a story. This is a memory.

Such transcendence is further emphasized by the diction used to describe the half-god mortals who fell in the river mud: ἠμίθέων γένος άνδρῶν. Here, the Hesiodic hēmítheoi, demigod, unusually replaces the conventional Homeric hērō. Cataloguing the fourth of the five Ages of Man, Hesiod names the heroes who were destroyed at Thebes and Troy, describing only this fourth race as hēmítheoi.

Hesiod’s chronicle of the successive generations of humanity, contemporary with Homer, is historically regressive, beginning with a distant Golden Age, passing through the Silver Age to the Bronze Age, with the Age of Heroes preceding what he describes as his own cruel and brutish Iron Age: “For now the race is indeed one of iron. And they will not cease from toil and distress by day, nor from being worn out by suffering at night… But Zeus will destroy this race of speech-endowed human beings too.”

Gregory Nagy interprets the Iliad’s shift in diction from Homeric to Hesiodic as indicative not only of the text’s awareness of a perspective which regards the heroes retrospectively, as Hesiod does, but also as an articulation which reaches beyond the boundaries of epic style: “Whereas hērōes is the appropriate word in epic, hēmítheoi is more appropriate to a style of expression that looks beyond epic… The diction of the Works and Days represents the Fourth Generation of Mankind in a manner that is appropriate to the heroes of epic tradition… and at the same time removed from the epic perspectives of the heroic age.”

Beyond epic – to what? Nagy does not specify. Before I suggest a possible direction, let’s look at another selection of passages from the Iliad.

Book I finds the wise Nestor advising the much younger Achilles and Agamemnon by comparing them harshly to the men of the past:

Yet be persuaded. Both of you are younger than I am.

Yes, and in my time I have dealt with better men than

you are, and never once did they disregard me. Never

yet have I seen nor shall see again such men as these were…

These were the strongest generation of earth-born mortals,

the strongest, and they fought against the strongest…

…against such men no one

of the mortals now alive upon earth could do battle.

Nestor is referring to heroes like Herakles and Theseus, who are so unimaginably superior that even the great Achilles and Odysseus wouldn’t be allowed to talk to them. While it’s certainly possible that this example is applied in a well-crafted rhetorical strategy to mollify the angry warriors, it’s altogether unlikely that the honey-voiced Nestor is simply fabricating the memory, particularly since this sentiment is echoed in subsequent passages.

When Phoenix rebukes Achilles’ pride, comparing his stubbornness to past heroes, he reminisces:

Thus it was in the old days also, the deeds that we hear of

from the great men…

Multiple sections gaze from within the narrative into the future, prophetically comparing the heroes with the men of Homer’s time, the latter summarily dismissed with the description as men are now:

Tydeus’ son in his hand caught

up a stone, a huge thing which no two men could carry

such as men are now, but by himself he lightly hefted it.

Also:

It was Sarpedon’s companion…

whom he struck with a great

jagged stone…

…A man could not easily hold it,

not even if he were very strong, in

both hands,

of men such as men are now.

And:

Hector snached up a stone…

…two men, the best in all a community,

could not easily hoist it up from the ground to a wagon,

of men such as men are now.

It’s significant that Homer does not merely tell us that Hector or Diomedes are strong in relation to other men, or even that it would take two men to accomplish what they accomplish. Homer contrasts them specifically with men “now,” men who cannot compare, not even if they’re the community’s best of the best of the best.

These remarks echo Nestor’s remembrances, but apply them to a span of centuries rather than just a few generations, resulting in a three-part regression in excellence: the men of Nestor’s youth were greater than the men who fought at Troy who were greater than the men of Homer’s time. This is obviously reminiscent of Hesiod’s formulation, since it is the Iron Age men whom Hesiod deplores who are the unfortunate men of the Homeric “now.”

The effect of these prophetic repetitions is to once again estrange the audience from the narrative with a self-conscious critique which itself prompts self-consciousness. The audience is reminded that it’s not only qualitatively removed from the heroic race, but also historically: this time was superior to our own and its men were better than our very best, but it is a vanished race, a lost society which has become, in Helen’s words, an object of song.

But what’s the purpose of this song?

Let’s now return to Nagy’s claim that the Iliad reaches beyond the epic. Beyond epic – to what? I would like to suggest that among the many epic, aesthetic, and cultural functions the Iliad undoubtedly serves, if we take into account both its emergence in relation to the rise of hero cults in the midst of the dawning 8th century recollection of a collapsed civilization and its self-aware critique of its own historical moment, what arises is a protean philosophy of history responding to the need for a collective remembering.

Homer’s historical vision is one of continuous regression, which is perhaps inevitable given the 8th century’s nascent awareness of the magnitude of what had been lost. One of several theoretical approaches to collective memory posits that a post-conflict society passes through the stages of memory and remembering, forgiveness, and acknowledgment. Here’s what I think:

The circulation and crystallization of the Iliad is how the 8th century first began to remember.

There are two bardic modes: the statement mode, which is a song that focuses on current events, and the possessive mode, a song of what has been that is preservatory in nature, working toward the possession of a commonly agreed past. The simultaneous rise of hero cults, tomb cults, and emergence of epic demonstrate the 8th century’s conscious need for such an explanation, and its deliberate search for heroes suggests not only the conviction that what has been lost was a more sophisticated society, but also that it is worth recovering.

Nestor’s description of his youth’s companions is not simply praise or recitation of facts; coupled with the evocation of the Greek wall’s demise, the Iliad acts as a sort of eulogy, mourning the vanished race.

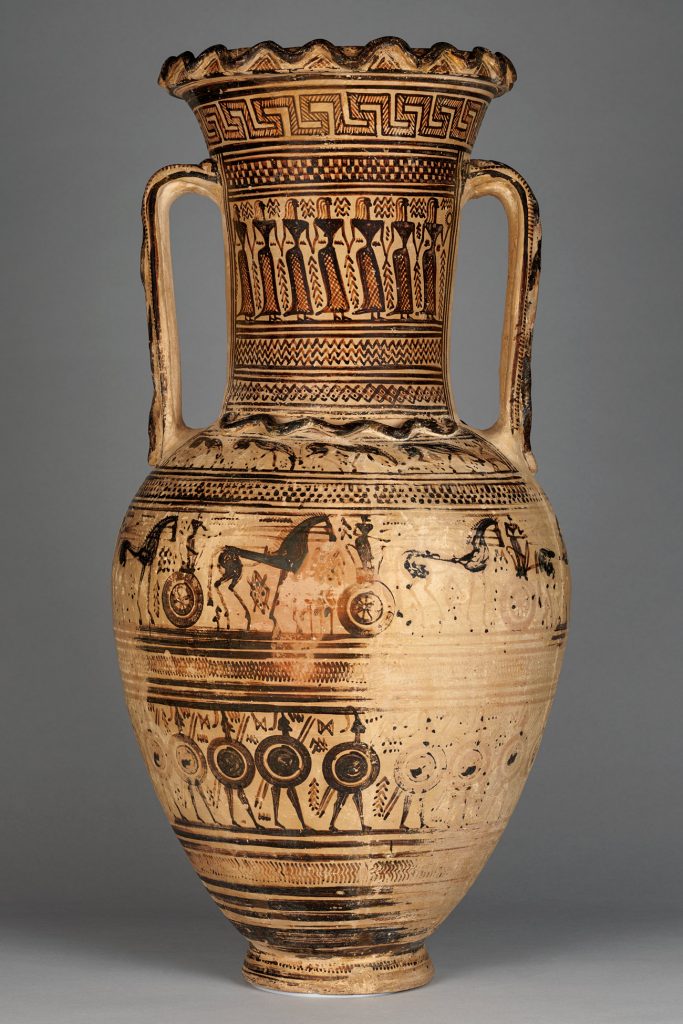

The epics’ congruence with the rise of geometric art also attests to this memorializing tendency, since the geometric age was characterized primarily by its funerary application to amphorae and other grave markers. This style of vase painting, aptly described by Cedric Whitman as “death conscious,” both eulogizes and attests, guarding against forgetfulness.

The possessive bardic mode is a historical mode, reconciling the men “now” to this unfortunate epithet by awarding them with a narrative which

*demystifies the palatial ruins,

*illuminates dim memories of exceptional people and splendid palaces,

*organizes recollections of chaos, depopulation, and violence into a coherent structure,

*and explains why it had to happen in just this way in a manner that renders it congruent with the emergent geometric art, hero cults, and tomb cults.

In brief, epic provides the community not only with a history, but also with a philosophy of history by means of which the Bronze Age collapse is recalled, forgiven, and acknowledged.

By thus informing its audience of how it stands in relation to its past, the Iliad performs the act of re-collecting, and in some sense even recovering what four centuries had obscured, healing the trauma of forgetting. This official history, established into Greek collective memory, can then be utilized for crystallizing and protecting Greek collective identity and furthering acts of socio-political import.

Of course, the history is as mythical as the validity of the political goals it gets appropriated by and the social structures it legitimizes, but as the manifestation of the spiritual allegiances of its culture, it is patently true.

You disagree? Go on, then.