On the Earliest Poetry and Being Less Boring

In twelve words: goddess loves her, goddess loves her not, goddess loves her, goddess loves…

In twelve words: goddess loves her, goddess loves her not, goddess loves her, goddess loves…

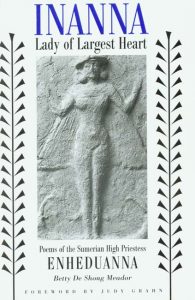

Are you surprised that the first known author in human history was a woman?

Daughter of the legendary rockstar conqueror and dynastic founder Sargon of Akkad, Enheduanna served as high priestess of the moon god’s cult in Ur, a super important religious center in Sumer.

Daughter of the legendary rockstar conqueror and dynastic founder Sargon of Akkad, Enheduanna served as high priestess of the moon god’s cult in Ur, a super important religious center in Sumer.

Religion and government were essentially the same thing in those days, and as high priestess, Enheduanna would’ve called the shots in Ur’s temple complex. This was somewhere around 2300 BCE.

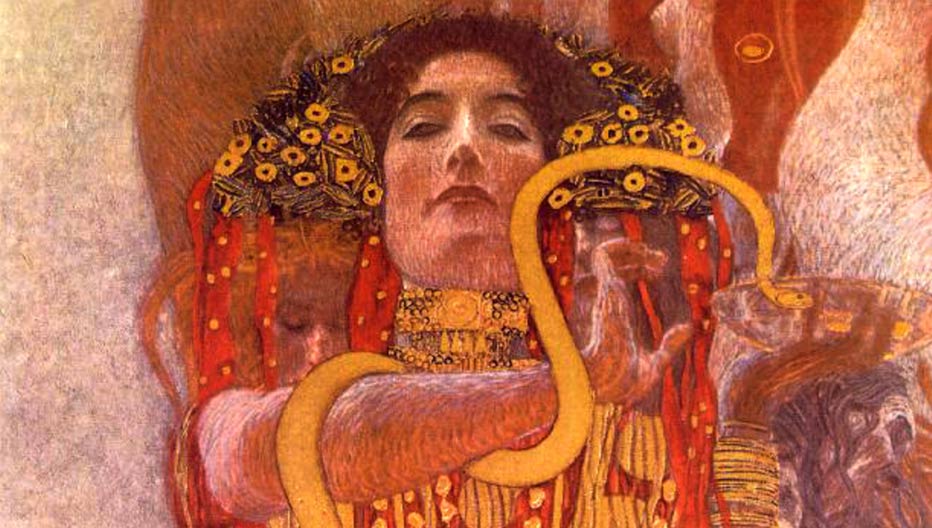

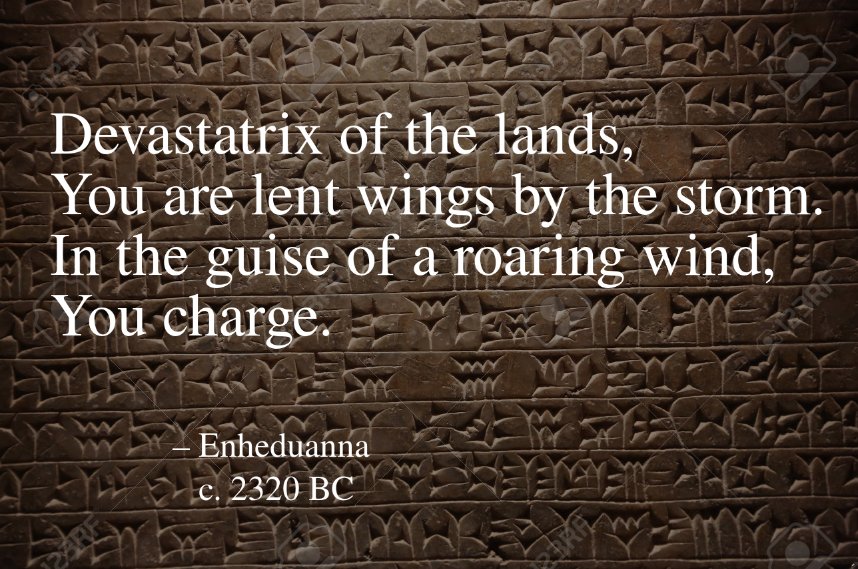

Just think: this princess, priestess, and poet was writing two thousand years before the Greek classical period. Her poetry influenced centuries of petitionary writing, from Homeric hymns to Biblical psalms. Looming imperiously at the very beginning of human literacy, Enheduanna’s most astonishing work is The Exaltation of Inanna, an autobiographical hymn to the Mesopotamian goddess of battle.

It describes how some jerk named Lugal-Ane staged a coup and exiled Enheduanna; after the furious goddess intervened on her behalf, Enheduanna was restored to her authoritative position.

It describes how some jerk named Lugal-Ane staged a coup and exiled Enheduanna; after the furious goddess intervened on her behalf, Enheduanna was restored to her authoritative position.

She also wrote about religion, war, and perhaps most tantalizingly, about herself. Her poems are intimate, personal, and straightforward in their evocation of inner experience.

We’re totally used to hearing modern poets complain about their lives, but more than 4,000 years separate us from Enheduanna.

I’ve encountered a few different translations of her writing – there aren’t many – and it’s always tempting to read her poems and say, “Oh my god, she’s just like me!” But she’s not. We don’t know her real name. We don’t even know the origin of the language she spoke and wrote. Moreover, we don’t know where the Sumerians themselves came from, what they looked like, or who their descendants are. Ancient Sumer is, in a profound sense, a lost world. We guess and infer, but the world’s first civilization is mostly an enigmatic, well-guarded secret.

For me, Enheduanna is associated with Nietzsche’s provocative question:

“Supposing that Truth is a woman – what then?”

Nietzsche thinks we’ve been approaching truth all wrong. Instead of doggedly pursuing her, philosophers should be charming and wooing her. Academic articles invariably begin with “This study aims to establish X, Y, and Z.” Timid, conscientious creatures, scholars are forever “aiming” to “establish” or “prove.” But maybe truth isn’t something to be established, discovered, or proven. Maybe truth is something to be seduced. Nothing destroys romance like the methodical argument, and no woman was ever driven mad with desire by a carefully drawn academic conclusion. Maybe we should swap our syllogisms and deductions for masks, perfumes, poems.

It’s not a coincidence that Enheduanna didn’t display her vast theological knowledge in tracts, lists, and summaries, like her contemporaries. She communicated with poetry.

Poets are always, always illusionists. Enheduanna was the very first, uniting the political and the religious, the sacred and the worldly, in art.

Ultimately, our image of Enheduanna and her lost kingdom is not only a matter of history, but also of aesthetics – we create the past just as much as we recover it. So let’s take our responsibility as artists more seriously by approaching scholarship more playfully. I’m convinced that Keats couldn’t have meant anything else when he wrote that “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.”

One thought on “On the Earliest Poetry and Being Less Boring”

If you haven’t already, I recommend watching Dr. Amanda Foreman’s ‘The Ascent of Woman’.